Classification rule

Given a population whose members can be potentially separated into a number of different sets or classes, a classification rule is a procedure in which the elements of the population set are each assigned to one of the classes.[1] A perfect test is such that every element in the population is assigned to the class it really belongs. An imperfect test is such that some errors appear, and then statistical analysis must be applied to analyse the classification.

A special kind of classification rule are binary classifications.

Contents |

Testing classification rules

Having a dataset consisting in couples x and y, where x is each element of the population and y the class it belongs to, a classification rule can be considered as a function that assigns its class to each element. A binary classification is such that the label y can take only a two values.

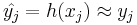

A classification rule or classifier is a function h that can be evaluated for any possible value of x, specifically, given the data  , h(x) will yields a similar classification

, h(x) will yields a similar classification  as close as possible to the true group label y.

as close as possible to the true group label y.

The true labels yi can be known but will not necessarily match their approximations  . In a binary classification, the elements that are not correctly classified are named false positives and false negatives.

. In a binary classification, the elements that are not correctly classified are named false positives and false negatives.

Some classification rules are static functions. Others can be computer programs. A computer classifier can be able to learn or can implement static classification rules. For a training data-set, the true labels yj are unknown, but it is a prime target for the classification procedure that the approximation : as well as possible, where the quality of this approximation needs to be judged on the basis of the statistical or probabilistic properties of the overall population from which future observations will be drawn.

as well as possible, where the quality of this approximation needs to be judged on the basis of the statistical or probabilistic properties of the overall population from which future observations will be drawn.

Given a classification rule, a classification test is the result of applying the rule to a finite sample of the initial data set.

Binary and multiclass classification

Classification can be thought of as two separate problems - binary classification and multiclass classification. In binary classification, a better understood task, only two classes are involved, whereas in multiclass classification involves assigning an object to one of several classes.[2] Since many classification methods have been developed specifically for binary classification, multiclass classification often requires the combined use of multiple binary classifiers.

Table of Confusion

When the classification function is not perfect, false results will appear. The example confusion matrix below, of the 8 actual cats, a function predicted that three were dogs, and of the six dogs, it predicted that one was a rabbit and two were cats. We can see from the matrix that the system in question has trouble distinguishing between cats and dogs, but can make the distinction between rabbits and other types of animals pretty well.

| Predicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat | Dog | Rabbit | ||

| Actual | Cat | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Dog | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Rabbit | 0 | 2 | 11 | |

When dealing with binary classifications this concepts are simpler

False positives

False positives result when a test falsely or incorrectly reports a positive result. For example, a medical test for a disease may return a positive result indicating that patient has a disease even if the patient does not have the disease. We can use Bayes' theorem to determine the probability that a positive result is in fact a false positive. We find that if a disease is rare, then the majority of positive results may be false positives, even if the test is accurate.

Suppose that a test for a disease generates the following results:

- If a tested patient has the disease, the test returns a positive result 99% of the time, or with probability 0.99

- If a tested patient does not have the disease, the test returns a positive result 5% of the time, or with probability 0.05.

Naively, one might think that only 5% of positive test results are false, but that is quite wrong, as we shall see.

Suppose that only 0.1% of the population has that disease, so that a randomly selected patient has a 0.001 prior probability of having the disease.

We can use Bayes' theorem to calculate the probability that a positive test result is a false positive.

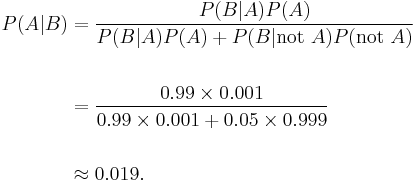

Let A represent the condition in which the patient has the disease, and B represent the evidence of a positive test result. Then, the probability that the patient actually has the disease given the positive test result is

and hence the probability that a positive result is a false positive is about 1 − 0.019 = 0.98, or 98%.

Despite the apparent high accuracy of the test, the incidence of the disease is so low that the vast majority of patients who test positive do not have the disease. Nonetheless, the fraction of patients who test positive who do have the disease (0.019) is 19 times the fraction of people who have not yet taken the test who have the disease (0.001). Thus the test is not useless, and re-testing may improve the reliability of the result.

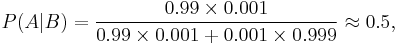

In order to reduce the problem of false positives, a test should be very accurate in reporting a negative result when the patient does not have the disease. If the test reported a negative result in patients without the disease with probability 0.999, then

so that 1 − 0.5 = 0.5 now is the probability of a false positive.

False negatives

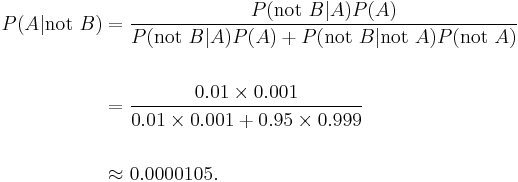

On the other hand, false negatives result when a test falsely or incorrectly reports a negative result. For example, a medical test for a disease may return a negative result indicating that patient does not have a disease even though the patient actually has the disease. We can also use Bayes' theorem to calculate the probability of a false negative. In the first example above,

The probability that a negative result is a false negative is about 0.0000105 or 0.00105%. When a disease is rare, false negatives will not be a major problem with the test.

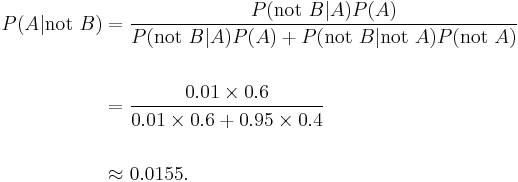

But if 60% of the population had the disease, then the probability of a false negative would be greater. With the above test, the probability of a false negative would be

The probability that a negative result is a false negative rises to 0.0155 or 1.55%.

Worked example

- Relationships among terms

| Condition (as determined by "Gold standard") |

||||

| Condition Positive | Condition Negative | |||

| Test Outcome |

Test Outcome Positive |

True Positive | False Positive (Type I error) |

Positive predictive value = Σ True Positive Σ Test Outcome Positive

|

| Test Outcome Negative |

False Negative (Type II error) |

True Negative | Negative predictive value = Σ True Negative Σ Test Outcome Negative

|

|

| Sensitivity = Σ True Positive Σ Condition Positive

|

Specificity = Σ True Negative Σ Condition Negative

|

|||

- A worked example

- The fecal occult blood (FOB) screen test was used in 2030 people to look for bowel cancer:

| Patients with bowel cancer (as confirmed on endoscopy) |

||||

| Condition Positive | Condition Negative | |||

| Fecal Occult Blood Screen Test Outcome |

Test Outcome Positive |

True Positive (TP) = 20 |

False Positive (FP) = 180 |

Positive predictive value

= TP / (TP + FP)

= 20 / (20 + 180) = 10% |

| Test Outcome Negative |

False Negative (FN) = 10 |

True Negative (TN) = 1820 |

Negative predictive value

= TN / (FN + TN)

= 1820 / (10 + 1820) ≈ 99.5% |

|

| Sensitivity

= TP / (TP + FN)

= 20 / (20 + 10) ≈ 67% |

Specificity

= TN / (FP + TN)

= 1820 / (180 + 1820) = 91% |

|||

Related calculations

- False positive rate (α) = type I error = 1 − specificity = FP / (FP + TN) = 180 / (180 + 1820) = 9%

- False negative rate (β) = type II error = 1 − sensitivity = FN / (TP + FN) = 10 / (20 + 10) = 33%

- Power = sensitivity = 1 − β

- Likelihood ratio positive = sensitivity / (1 − specificity) = 66.67% / (1 − 91%) = 7.4

- Likelihood ratio negative = (1 − sensitivity) / specificity = (1 − 66.67%) / 91% = 0.37

Hence with large numbers of false positives and few false negatives, a positive FOB screen test is in itself poor at confirming cancer (PPV = 10%) and further investigations must be undertaken; it did, however, correctly identify 66.7% of all cancers (the sensitivity). However as a screening test, a negative result is very good at reassuring that a patient does not have cancer (NPV = 99.5%) and at this initial screen correctly identifies 91% of those who do not have cancer (the specificity).

Measuring a classifier with sensitivity and specificity

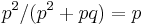

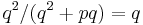

Suppose you are training your own classifier, and you wish to measure its performance using the well-accepted metrics of sensitivity and specificity. It may be instructive to compare your classifier to a random classifier that flips a coin based on the prevalence of a disease. Suppose that the probability a person has the disease is  and the probability that they do not is

and the probability that they do not is  . Suppose then that we have a random classifier that guesses that you have the disease with that same probability

. Suppose then that we have a random classifier that guesses that you have the disease with that same probability  and guesses you do not with the same probability

and guesses you do not with the same probability  .

.

The probability of a true positive is the probability that you have the disease and the random classifier guesses that you do, or  . With similar reasoning, the probability of a false negative is

. With similar reasoning, the probability of a false negative is  . From the definitions above, the sensitivity of this classifier is

. From the definitions above, the sensitivity of this classifier is  . With more similar reasoning, we can calculate the specificity as

. With more similar reasoning, we can calculate the specificity as  .

.

So, while the measure itself is independent of disease prevalence, the performance of this random classifier depends on disease prevalence. Your classifier may have performance that is like this random classifier, but with a better-weighted coin (higher sensitivity and specificity). So, these measures may be influenced by disease prevalence. An alternative measure of performance is the Matthews correlation coefficient, for which any random classifier will get an average score of 0.

The extension of this concept to non-binary classifications yields the confusion matrix.

See also

References

- ^ Mathworld article for statistical test

- ^ Har-Peled, S., Roth, D., Zimak, D. (2003) "Constraint Classification for Multiclass Classification and Ranking." In: Becker, B., Thrun, S., Obermayer, K. (Eds) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 15: Proceedings of the 2002 Conference, MIT Press. ISBN 0262025507